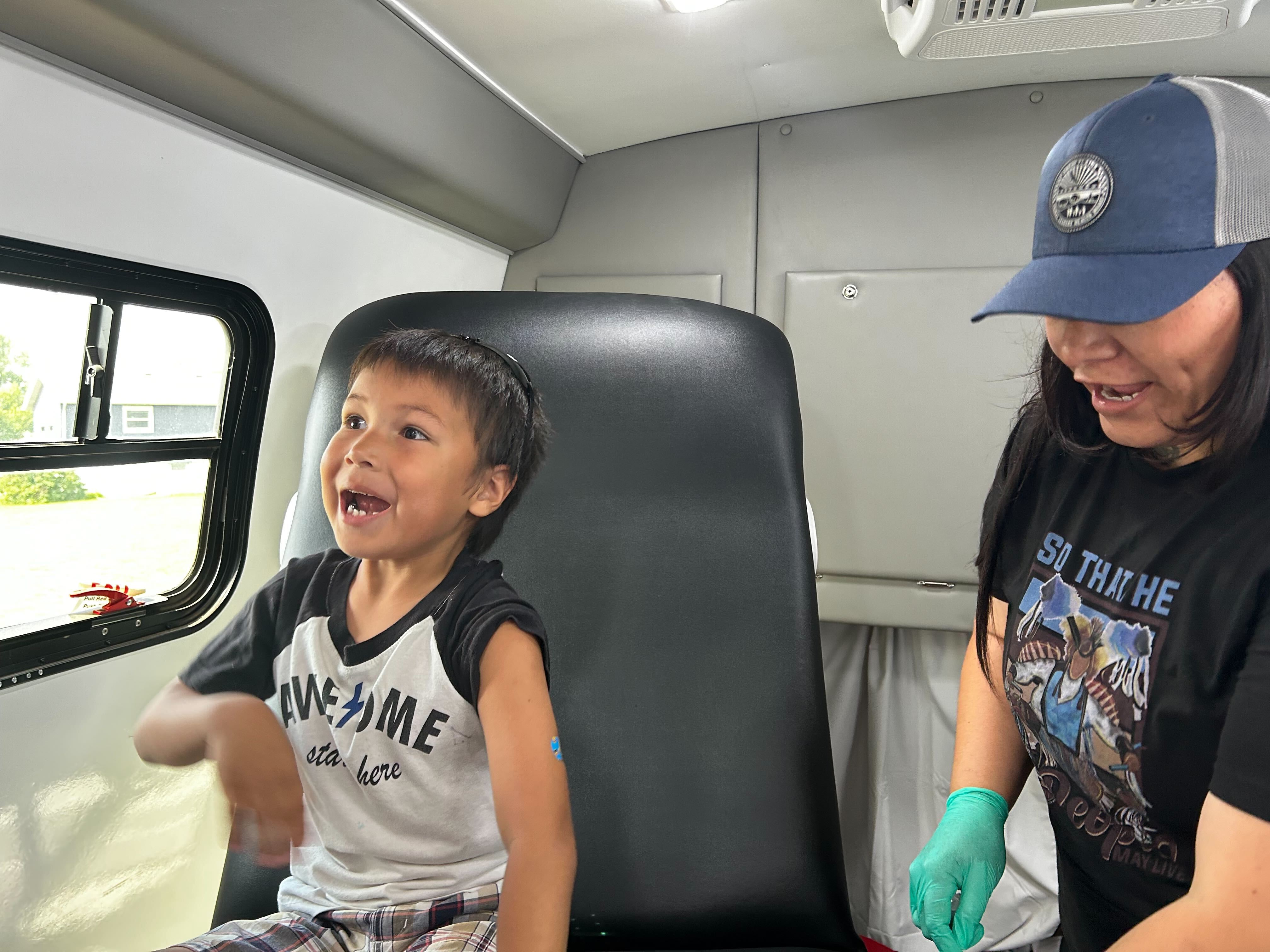

RAPID CITY, S.D. — Cassandra Palmier had been meaning to get her son the second and final dose of the measles vaccine. But car problems made it difficult to get to the doctor.

So she pounced on the opportunity to get him vaccinated after learning that a mobile clinic would be visiting her neighborhood.

“I was definitely concerned about the epidemic and the measles,” Palmier, a member of the Oglala Sioux Tribe, said at the June event. “I wanted to do my part.”

So did her son, Makaito Cuny.

“I’m not going to be scared,” the 5-year-old announced as he walked onto the bus containing the clinic and hopped into an exam chair.

Makaito sat still as a nurse gave him the shot in his arm. “I did it!” he said while smiling at his mother.

The vaccine clinic was hosted by the Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board, which serves tribes across Iowa, Nebraska, and the Dakotas. It’s one way Native American tribes and organizations are responding to concerns about low measles vaccination rates and patients’ difficulty accessing health care as the disease spreads across the country.

Meghan O’Connell, the board’s chief public health officer, said it is also working with tribes that want to host vaccine clinics.

Elsewhere, tribal health organizations have launched social media campaigns, are making sure health providers are vaccinated, and are reaching out to the parents of unvaccinated children.

This spring, Project ECHO at the University of New Mexico hosted an online video series about measles aimed at health care professionals and organizations that serve Native American communities. The presenters outlined the basics of measles diagnosis and treatment, discussed culturally relevant communication strategies, and shared how tribes are responding to the outbreak.

Participants also strategized about ways to improve vaccination rates, said Harry Brown, a physician and an epidemiologist for the United South and Eastern Tribes, a nonprofit that works with 33 tribes in the Atlantic Coast and Southeast regions.

“It’s a pretty hot topic right now in Indian Country and I think a lot of people are being proactive,” he said.

Measles can survive for up to two hours in the air in a space where an infected person has been, sickening up to 90% of people who aren’t vaccinated, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The U.S. has had 1,319 confirmed cases of measles this year as of July 23, according to the CDC. It’s the largest outbreak in the U.S. since 1992. Ninety-two percent of the 2025 cases involve unvaccinated patients or people with an unknown vaccination status. Three people had died in the U.S. and 165 had been hospitalized as of July 23.

O’Connell said data on Native Americans’ vaccination rates is imperfect but that it suggests a lower percentage of them have received measles shots than the overall U.S. population.

The limited national data on measles vaccination rates for Native Americans is based on small surveys of people who self-identify as Native American. Some show that Native Americans have slightly lower measles vaccination rates, while others show significant gaps.

Data from some states, including South Dakota and Montana, shows that Native Americans are less likely than white children to be vaccinated on schedule.

The national measles vaccination rate is significantly lower for Native Americans who use the mostly rural Indian Health Service. About 76% of children 16 to 27 months old had gotten the first shot, according to data collected by the agency during recent patient visits at 156 clinics. That’s a 10-percentage-point drop from 10 years ago.

But the IHS data shows that its patients are at least as likely as other children to have received both recommended measles shots by the time they’re 17. O’Connell said it’s unclear if currently unvaccinated patients will continue the trend of eventually getting up to date on their shots or if they will remain unvaccinated.

The immunization rate is probably higher for older children since schools require students to get vaccinated unless they have an exemption, Brown said. He said it’s important that parents get their children vaccinated on time, when they’re young and more at risk of being hospitalized or dying from the disease.

Native Americans may have lower vaccination rates due to the challenges they face in accessing shots and other health care, O’Connell said. Those on rural reservations may be an hour or more from a clinic. Or, like Palmier, they may not have reliable transportation.

Another reason, O’Connell said, is that some Native Americans distrust the Indian Health Service, which is chronically underfunded and understaffed. If the only nearby health care facility is run by the agency, patients may delay or skip care.

O’Connell and Brown said vaccine skepticism and mistrust of the entire health care system are growing in Native American communities, as has occurred elsewhere nationwide.

“Prior to social media, I think our population was pretty trustful of childhood vaccination. And American Indians have a long history of being severely impacted by infectious disease,” he said.

European colonizers’ arrival in the late 1400s brought new diseases, including measles, that killed tens of millions of Indigenous people in North and South America by the early 1600s. Native Americans have also had high mortality rates in modern pandemics, including the 1918-20 Spanish flu and covid-19.

The Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board reacted quickly when measles cases began showing up near its headquarters in South Dakota this year. Nebraska health officials announced in late May that a child had measles in a rural part of the state, close to the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Then, four people from the Rapid City area got sick later that month and into the middle of June.

“Our phones really rang off the hook” once that news came out, said Darren Crowe, a vice president at the board’s Oyate Health Center in Rapid City. He said parents wanted to know if their children were up to date on their measles vaccines.

Crowe said the health board ordered extra masks, created a measles command team that meets daily, and called parents when its online database showed their children needed a shot.

Brown praised that approach.

“It takes a concerted outreach effort that goes individual to individual,” he said, adding that his organization helped the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas with similar efforts.

Brown said reaching specific families can be a challenge in some low-income Native American communities, where many people’s phone numbers frequently change since they use temporary prepaid plans.

Once a health worker reaches a parent, Brown said, they should listen and ask questions before sharing the importance of the vaccine against measles, mumps, and rubella.

“Rather than trying to preach to somebody and beat them over the head with data or whatever to convince them that this is what they need to do, you start out by finding out where they are,” he said. “So, ‘Tell me about your experience with vaccination. Tell me what you know about vaccination.’”

Most people agree to immunize their children when presented with helpful information in a nonjudgmental way, Brown said.